In 1513, Leonardo DaVinci may have drawn the first illustration of a congenital heart defect (CHD). But he was ahead of his time. While CHDs have existed as long as people have, our ability to study them has been limited. And even once we could study them, it would be decades before we developed effective congenital heart defect treatment.

Surgery to treat CHD wasn’t attempted until 1938. And up through 1980, if you were born with a CHD, you were more likely to die than not. Only 15% of children born with CHD lived into adulthood. Most died in the first year.

Modern CHD care has come a long way. Today, more than 90% of children born with CHDs live into adulthood. And the future continues to look brighter as we uncover more ways to treat CHD.

But there were a lot of milestones along the way that are worth remembering. Much like our understanding of cancer, looking at the full timeline shows how far we’ve come, and inspires hope for how much more we can do.

Timeline of Congenital Heart Defect Treatment

Here's a snapshot:

- 1858: First work creating categories of CHDs

- 1908: Chapter on Congenital Cardiac Disease Published in Modern Medicine

- 1938: First Surgical Repair of CHD

- 1944: First Surgical Repair of Critical CHD

- 1955: Heart Bypass Machine Emerges- Allowing for More Complex Procedures

- 1968: Fontan Procedure Creates Hope for Single Ventricle Defects

- 1980: Norwood and Glenn Procedure Added to Fontan for Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome Treatment

- 1984: First Pediatric Heart Transplant

1800-1920s: Understanding & Categorizing CHD

In 1858, Thomas Bevill Peacock published “On Malformations of the Human Heart.” In it, Peacock tried to classify CHD into categories. He also recognized something we now know to be true: CHD runs in families.

Genetics, though, wasn’t a fully developed field. Peacock chalked up this familial tendency to “mental impressions or shocks” moms had during pregnancy.

Approximately 50% of children born with Down syndrome will also be born with a congenital heart defect.

In 1908, Maude Abbott contributed a chapter to Osler’s “Modern Medicine” on Congenital Cardiac Disease. She agreed with Peacock that family history played a role.

Abbott also realized something new: Some conditions were more likely to go along with CHD. Abbott noticed Down syndrome seemed to be related, something we’ve confirmed to be true.

1938: The First Surgery for a Congenital Heart Defect

Most early medical interest focused on categorizing CHD and hoped to find ways to prevent it. But they quickly discovered that CHD usually isn’t preventable.

So, the next hurdle was how to fix it.

In 1938, Robert Gross, MD, performed the very first patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) closure. The patient was a 7-year-old girl named Lorraine Sweeney. Lorraine’s PDA left her exhausted and put her at risk for an early death. Gross, defying his boss, did the surgery.

It was the first surgical correction of a CHD in a human. And it was an overwhelming success. Lorraine lived a vibrant and full life. While most PDA patients at the time passed away while still young, she lived to the age of 89 and became a great-grandmother. She shared her account shortly before her death.

1940s-1950s: Surgical Innovation & Correcting CHD

Gross’ surgery was a huge first step. But he figured out how to repair one form of CHD. There are over 30 unique forms. Many children are born with multiple defects.

In our current classifications, the biggest distinction made is between critical and non-critical heart defects. Critical defects need urgent treatment, or they can result in death. While PDAs are serious, they’re not immediately life-threatening. But just 6 years later, inspired by Gross’ success closing a PDA, a critical CHD was corrected with surgery.

Helen Taussig, MD, needed a way to save her “blue babies.” These babies had a more critical CHD, tetralogy of Fallot. And because their heart couldn’t keep their blood oxygenated, they did actually turn blue. In that first PDA surgery, Taussig saw a way to save these babies. She designed a shunt.

Taussig first approached Robert Gross. But he told her he had his hands full with the PDA.

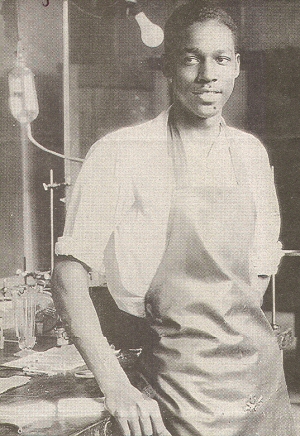

In 1944, Helen Taussig, in partnership with surgeons Alfred Blalock and Vivien Thomas, first tried what is now known as the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt. This procedure is still used today for conditions like pulmonary atresia and tetralogy of Fallot.

By the 1950s, Blalock had performed over 1,000 CHD correctional surgeries. He even developed a technique for addressing transposition of the great arteries, another critical CHD.

Continued CHD surgical innovation was made possible by the heart bypass machine, which was introduced in 1955. The bypass machine allowed for safer and more intricate surgeries.

On paper, this period might seem like a golden era of surgical innovation. And it was. But the mortality rate was still high, both from surgical complications and from the lack of congenital heart defect treatment options. The next decades focused on addressing the most fatal congenital heart defects and improving surgical safety.

1970s-1980s: Hope for Patients with the Most Serious CHDs

Single ventricle defects are some of the most serious forms of CHD. In these conditions, part of the heart is smaller, missing, or undeveloped. This means the heart can’t pump blood to both the lungs and the body. Single ventricle defects account for 7.7% of all CHDs.

Single ventricle defects include conditions like:

- Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- Pulmonary atresia

- Tricuspid atresia

- Ebstein’s anomaly

Initially, the only treatment available for these patients was a heart transplant. But in 1968, the Fontan procedure was first introduced.

Frances Fontan was deeply affected by a teenage patient he had with tricuspid atresia. Sadly, the patient died, which drove Fontan to work on this procedure. The first patient he performed it on also had tricuspid atresia and survived it, thanks to this operation.

The initial procedure created a shunt that sent blood from the body through the lungs, bypassing the heart. This allowed a single ventricle to send blood to the body and lungs simultaneously.

The Fontan saved thousands of lives. But it became more valuable when paired with the Glenn and Norwood procedures. These two procedures “set the stage” for the Fontan. This staged heart reconstruction is necessary for children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS).

Largely considered one of the most critical CHDs, more than 1,000 babies are born in the United States with HLHS every year. Without surgery, most babies die within two weeks of being born.

1980s-1990s: Pediatric Heart Transplant Gets Its Start

While heart transplants started in 1967, it took longer to succeed for pediatric patients. The topic was considered controversial.

The first neonatal heart transplant was attempted in 1984. Unfortunately, it was only a short-lived success. But later that year, a 2-year-old girl also received a heart transplant. Now 42, her original donor’s heart continues to support her active and thriving life.

This first success opened the floodgates. While only 10 pediatric patients received heart transplants in 1985, in 1990, 118 received transplants. UVA Health Children’s was one of the children’s hospitals leading the way in this important milestone. In 1991, we performed our first pediatric heart transplant.

2000-2010: Minimally Invasive Techniques & Adult Congenital Heart Defect Care

By the early 2000s, the first wave of children who had survived critical CHDs became adults. Adult CHD care became a new and important field. Cardiologists trained in CHDs help adult patients care for their unique hearts. This is especially important through events like pregnancy, which can strain the heart.

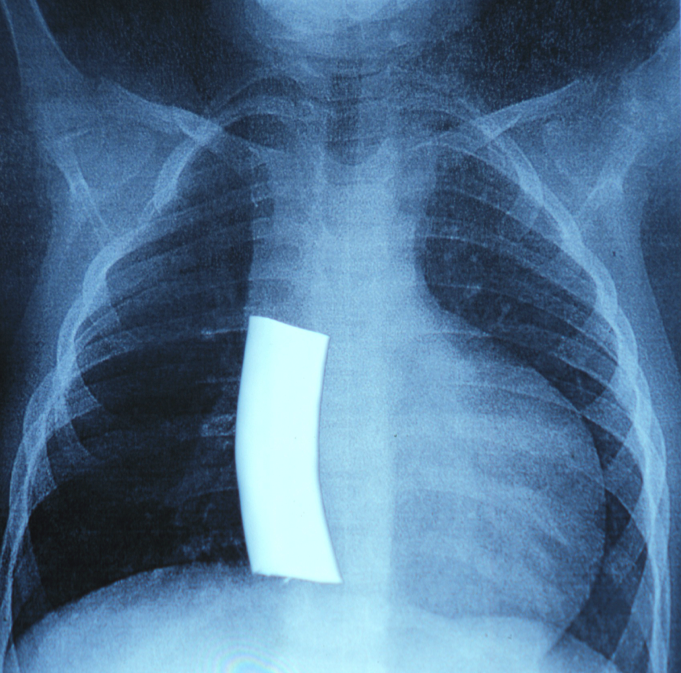

For infants with CHDs, the early 2000s saw a greater focus on interventional catheterization. Catheterization procedures are minimally invasive congenital heart defect treatments. This type of procedure means faster healing and fewer complications.

Many CHDs now have minimally invasive treatment options. We now perform a PDA closure, the first CHD surgery performed, with a catheter. And while Robert Gross’ original procedure took nearly 3 hours, it now takes less than an hour.

2010-Today: Better Prevention, Better Treatment, & Better Outcomes

From a certain death to living and thriving, CHD care has come a long way.

But that doesn’t mean there aren't more advancements ahead. In particular, how can we improve the quality of these children’s lives? Programs like our neurocardio clinic help children with CHD thrive.

At UVA Health Children’s, we’ve been pushing the field of CHD care forward, through:

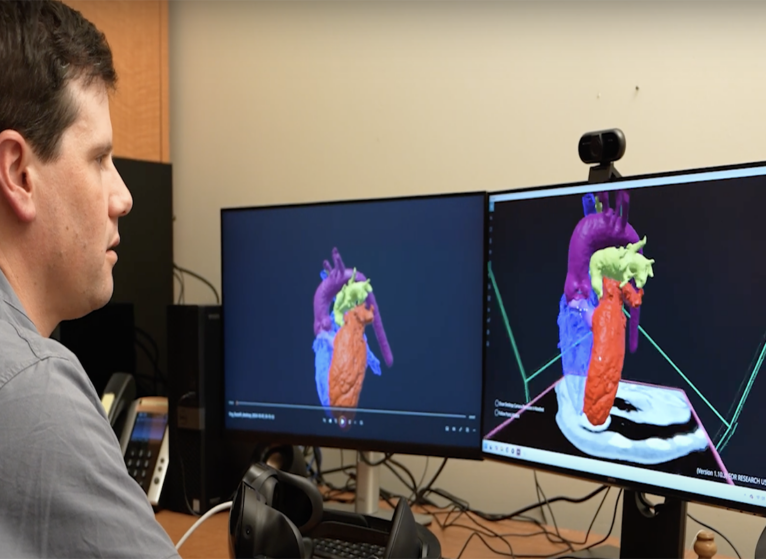

- 3D Modeling and VR simulation of surgeries

- Treating developmental differences in children with CHD

- Improving pediatric heart transplant

- Partial pediatric heart transplant

- Early identification and support through cardio genetics programs

Better Futures for Children with CHD

Many of the first children to survive critical CHD are adults now. Often, they’ve shared their experiences to help other families find hope. While CHD is still a serious diagnosis, there are congenital heart defect treatment options now that didn’t exist even 50 years ago.