LGBTQ health — is it really an issue?

Not many of us enjoy going to the doctor or visiting the emergency room. You’re sick, you’re vulnerable, and the number of unknowns can be stressful.

Now imagine that on top of those worries, you also have no way to predict if the registration staff, the nurses and doctors you meet, and the other patients in the waiting room will be kind or even just civil to you. What if they don’t listen? What if they call you the wrong name? What if they think you’re something you’re not? What if they ask embarrassing questions — or the wrong ones?

Maybe you’ve had bad experiences with doctors who said you were sick for being gay. Maybe you’ve experienced rejection from parents, community leaders and people in your hometown because of who you are, how you dress, and who you love. Facing any kind of stranger can feel risky. Should you even go?

How would you answer that question?

For many gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people the safest answer is no.

Bias & Stigma: Barriers to LGBTQ Health

This aversion to going to the doctor isn’t just the result of a misperception. Studies have shown the existence of a long history of social stigma, bias and discrimination faced by LGBTQ people in the healthcare setting. These continue to lead to health disparities that put these patients at higher risk for certain conditions. Don’t think doctors are biased? A 2015 National Institutes of Health study reported 80 percent of first-year medical students expressing some form of bias against lesbians and gay men.

Is it any surprise LGBTQ people avoid the doctor?

Not to Catherine Casey, MD, primary care doctor at UVA. This is, in fact, the reason she got interested in LGBTQ health. “When I was a medical student, my good friends were gay, and they would only see a doctor who was openly gay. They expressed difficulties going to student health, where they weren’t sure how people were going to receive the news that they were gay or know how to treat them.”

And even today, Elke Zschaebitz, nurse practitioner at the Elson Student Health Center, has “clients who need to go to the UVA Infectious Diseases Clinic – but won’t, because there’s still a stigma.”

In the Closet in the Clinic

Not all LGBTQ people avoid seeking care due to the experience or expectation of bias. Some go, but then are reluctant to reveal their sexual orientation or gender identity to their providers. This silence can have negative consequences on care.

Ken White, PhD, NP, both the associate dean for strategic partnerships and innovation at the School of Nursing and a palliative care nurse practitioner, notes that “some diseases are missed altogether because they haven’t done a complete health history, a sexual identity-specific health history.”

A gay man himself, White says, “I’ve never had a physician ask me about my sexual history.”

Frank conversations help providers understand an individual’s health risks. One of the reasons LGBTQ people have increased risks stems from the lack of this critical piece of the healthcare experience.

Slowly Making Progress: New Guide for Transgender Care

Within the LGBTQ community, each identity faces distinct health and wellness issues. A new guide addresses the unique medical challenges faced by transgender patients.

Published in July 2019 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the guide aims to give primary care providers the knowledge and tools to make their trans patients comfortable and help them reach their health goals. It covers hormone treatments, surgical plans and how to support transgender patients in both their decision-making regarding care and their long-term health plans. It gives recommendations regarding mental health evaluation, substance abuse care and other barriers to wellness faced by transgender patients.

The guide doesn’t just address medical issues. It also provides definitions to common terminology and addresses legal and social issues faced by the transgender population. It recommends best practices for creating welcoming clinical environments for trans patients, including staff trainings and updated bathroom policies.

“I was excited to see this article come out in a widely distributed, prestigious journal. I think it speaks to the growing awareness of the importance of providing competent care to transgender, nonbinary, and intersex patients,” said Casey. “These guidelines are consistent with our approach for adult transgender services.”

Increased Health Risks

LGBTQ people who avoid or cannot access inclusive healthcare suffer from a lack of appropriate care.

Some issues and statistics that result:

- Lesbians fail to practice safe sex, such as using condoms with sex toys, exposing themselves unnecessarily to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including HPV.

- Lesbians are less likely to get pap smears or other cancer prevention services.

- Lesbians have a higher rate of heart disease due to higher instances of obesity and smoking.

- Gay men have an increased risk for prostate, testicular and colon cancer.

- Gay men don’t usually get anal pap smears, even though they are at a high risk for contracting HPV that leads to anal cancer (see CDC guidelines).

- Gay men also continue to be at a higher risk for HIV and STDs.

Minority Stress & Mental Health

Another factor in LGBTQ health: Minority stress, defined as the discrimination, stigma and internalized homo- and transphobia experienced by LGBTQ individuals in their daily lives.

LGBTQ people also experience violence at higher rates than others, as well as higher rates of intimate partner violence.

Researchers point to minority stress as the reason the LGBTQ population experiences more:

- Alcohol use

- Smoking

- Risky behaviors

- Obesity

- Stress

- Depression

- Suicide

Aging Issues

Minority stress and alcohol and substance abuse extend into the older population, too. White talks about the aging LGBTQ generation having concerns that may be overlooked. “Younger people have difficulty appreciating that a lot of older people have been estranged from their families, and they are often alone. The elderly LGBTQ population mostly don’t have children. Who comes around to see them? Who takes them to their appointments?”

He’s also known of patients who experience “disrespect in nursing homes, regarding privacy issues, their sexual identity; they’re made fun of,” which only adds to the distress and loneliness.

Considerations: Making it LGBTQ Inclusive

Using Inclusive Language

Casey has learned a great deal while providing care over time to LGBTQ patients.

Casey explains that, to her, the goal of a primary care doctor is to “evolve with the times to meet the needs of our patients. This can be challenging, as the language is constantly changing and in flux and while we do our best to use the most respectful, currently acceptable language, we can fall behind.”

For example, the term “queer”: “Older generations of people have experienced that word as a very stigmatizing word, whereas others these days seem to really embrace that term and use it in referring to themselves. I use language-mirroring in that case. I have to get over my own uncomfortable feelings. If ever in any doubt, I always just ask.”

Being Sensitive and Stubborn With LGBTQ Health Screenings

Casey has also learned that applying statistics to patients can require finely honed interpersonal skills. It’s a balancing act, she says, covering the necessary bases and listening to individual’s particular needs.

Casey tells the story of seeing a trans person in her clinic who seemed well-balanced, causing her to struggle with following the usual protocol of screening for suicide risk. “But I had to,” she explains. “43 percent of trans adults attempt suicide. I would be a bad doctor if I didn’t ask.”

Chris Peterson, MD, emphasizes universal screening for everyone who comes to the Elson Student Health Clinic. Still, she notes, “Sometimes you need to delve a little deeper, press a little harder, when someone has a risk factor. You have to pay a lot of attention.”

She gives the example of breast cancer screenings. “For any woman who’s never had a full-term pregnancy, the risk of breast cancer is 30 percent higher. Everyone needs that screen, but you need to pay particular attention to people who don’t want the screen but are at higher risk.”

One thing Zschaebitz looks for is misuse of prescriptions: Transgender women, for instance, “take regular birth control with a prescription. I have to tell them this is dangerous.”

Asking the Right Questions

“Women who self-identify as a lesbian may also have or have had a male partner or are planning or have had a pregnancy. You can’t assume everyone needs contraception or that they don’t need it,” says Zschaebitz.

Of course, questions can be helpful or not, depending on a number of factors and nuances that may become complex. Which is why, as White sees it, healthcare providers need more guidelines around how to respectfully treat LGBTQ patients. He points out that, in the healthcare setting, intrusive questions can be harmful.

“I heard an awful story about a transgender male who was badgered about the pap smear question and menstrual history and all kinds of things. Was that critical? How do you handle that? How do you ask the question about birth control? What is intrusive and what is bona fide information you need to know for a health history? We have to give guidelines to people who just don’t know.”

Training That Creates a Safe Space

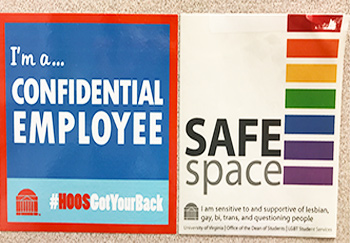

Many UVA providers have taken safe-space training from the UVA LGBTQ Center. This program introduces concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity, statistics, facts and terminology. It also provides a window into the experiences LGBTQ people have coming out, including discrimination and legal issues.

Making it Visual

Peterson makes sure to have a logo or safe-space sticker in the room to make patients “feel more comfortable asking questions and telling the stories they want to tell. If you’re not working with the whole person, if they don’t feel safe with you,” then the advice or services offered will be inadequate.

Casey wears a rainbow on her badge. “It’s a quiet, unobtrusive way to say, you can open up to me. It helps open up a conversation.”

Nonjudgment and Acceptance

Zschaebitz feels the greatest thing she does for her patients is offer acceptance. “I have adult friends who were rejected by their parents. It hurts. I know they appreciate that I accept them right away. And that’s what I give to my patients, too.”

“As a primary care doctor,” Casey says, “I wanted to be someone who people knew was going to be caring, nonjudgmental and competent.”

In fact, Zschaebitz admits she’s a bit biased toward her LGBTQ patients. “I try to engage them more. I care about them, and I really do go out of my way to take my time. This means making more conversation to connect with them. In the end we all have hurts, we all have illness, we all have deaths and births and happiness, we’re all human. So I try to make it a human experience.”

Policies From the Top

White, who chairs the LGBTQ forum of the American College of Healthcare Executives, has a national perspective on how social change has pushed organizations to make the hospital environment more welcoming to LGBTQ patients.

Hospital leaders didn’t always prioritize LGBTQ health issues. But now, “in an era of diversity and inclusion, they’re recognizing it’s an important segment we need to serve.”

He’s witnessing a growing trend on the part of hospitals nationwide to “develop patient care and employee policies and procedures that are inclusive.”

In 2007, the Human Rights Campaign created the Health Equality Index, a tool that measures and guides this effort by setting guidelines on providing equitable care and adopting LGBTQ-inclusive patient, visitation and employment policies. UVA Health System is currently in the process of using this index to help identify best practices and where gaps exist, in order to develop plans to fix them. Included in this effort: modifying Epic, the electronic medical record system, to collect necessary information that captures preferred name, pronoun and gender identity.

“Even Virginia, when you look at all the states, is making remarkable improvement,” White notes. Here at UVA, he recalls an episode of a transgender colleague coming back to work after sex-affirming surgery. “The whole unit came together, talked about how to be respectful in welcoming the staff member back.”

An Environmental Shift

Peterson explains that in her 30-year career with UVA, she’s witnessed the evolution of condom use and HIV testing from being totally absent to completely routine. And the student health clinic, which used to just maintain hormone prescriptions for transgender students, will soon start initiating transgender care. This means transgender students can receive the counseling, medical care and hormone treatments they need to fully be themselves.

“Cultural changes, the acceptance, so much better than it was, in terms of relationships, marriage, screening, healthcare. Wonderful change in society,” she says.

Another initiative at UVA underscores this shift: A recently formed advisory committee brings leaders from across the Health System together to address gaps in training, policies and practice. The group aims to take concrete steps towards improving the patient experience for LGBTQ patients.

For Casey, continuing to foster the inclusive environment here at UVA requires, along with training and policies, a certain amount of grace. “I make mistakes all the time. That’s one of the lessons that I feel is most valuable. Another doctor who is gay and works with the transgender population told me, ‘You will make mistakes, it’s inevitable, and the important thing is to just apologize, correct yourself, and move on. You’re not expected to be perfect, nobody is.’”

We originally published this blog post in 2017 and updated it in November 2019.

Do you guys offer services for Sex reassignment surgery (male-to-female) ??

Dr. Nancy McLaren, who works in the Transgender Health Clinic, says: Not yet. There is a surgeon looking into being trained. I usually refer people to someone in Philadelphia, New York or Chicago. I’m happy to see you and then do a referral /give you information. People usually need several letters for the surgery – so it can be helpful for us to get to know them. You can make an appointment with Dr. McLaren here: https://uvahealth.com/locations/profile/teen-and-young-adult-health-center or by calling: 434.243.3675